Amalgamation and America (Episode 5)

What really made people hate Frances Wright?

Nashoba, Frances Wright’s intentional community designed to end slavery, went sideways, as we’ve explored in the last few episodes. The physical abuse of the enslaved there might be what we find most upsetting nowadays, but what really got people worked up about Nashoba at the time?

It’s something called “amalgamation,” the mixing of people of different racial backgrounds. Frances Wright openly advocated this mixing and saw it as the future of America. Many people were outraged.

In this episode, we go deep into the context of this tension, a long-standing source of anxiety for White Americans and too often a justification for curtailing the rights of African-Americans. The actual history of interracial relationships under slavery, even in the free Northern States, was complicated, more so than we usually hear in history class, and it’s still reverberating today, though as a nation and as people, we’ve made progress.

Our expert guests this week are historians Leslie M. Harris (Northwestern University) and Amrita Myers (Indiana University).

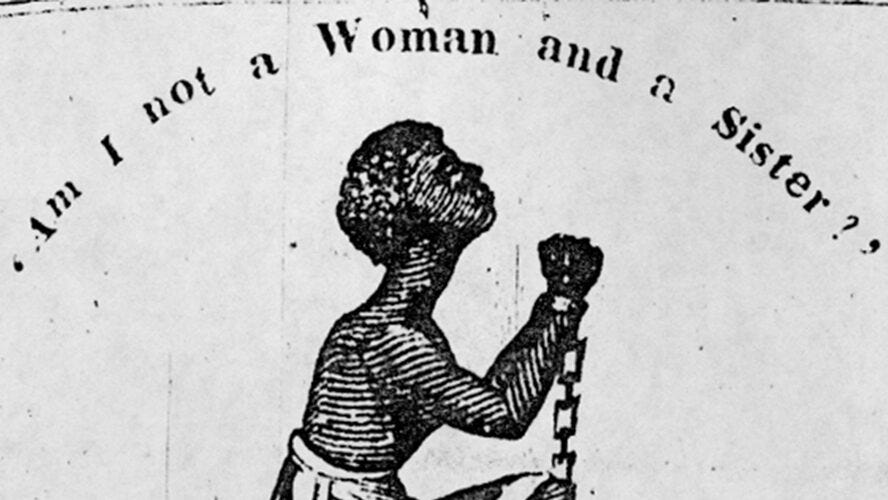

Leslie goes into the meaning and context of amalgamation and how it was weaponized against anti-slavery organizers–and what it says about America’s anxieties surrounding race and class. See an example of the kind of racialized White fever-dream image of amalgamation’s menace that Harris refers to here. (Warning: racially derogatory depiction)

Harris’ groundbreaking work on New York’s complex relationship with slavery has impacted the way we talk about this entire era and its resonances. (We highly recommend her book In the Shadow of Slavery.) Her nuanced, outspoken scholarship has been instrumental in painting meticulous portraits of African-American lives and arguing for historically painstaking approaches to Early American history. (See her fascinating piece in Politico examining some of the bolder claims in the 1619 Project, for which she consulted.)

Amrita helps us explore the life and times of Julia Chinn, an enslaved woman who was also the wife of one of America’s early Vice Presidents–though he never freed her. (Check out her book on Julia Chinn here.) She helps us glimpse what we need to do as historians to restore the stories of women like Chinn, which are vital to understanding America’s past. You can read more about Amrita’s indepth approach to excavating Julia’s life story in this engaging interview here.

Amrita’s methods point to an important aspect of researching this part of American history. She triangulates as many elements as she can, but she also asks what’s missing and why. As she put is in the interview linked above, she found she needed to “…interrogate silence. As historians of Black women, this is what we must do because of the gaps in the written record. What is missing can often tell us as much as what is present. Asking ‘why’ a person isn’t in a document (or an archive) can be an incredibly fruitful line of inquiry.”

We also mention another scholar who has peeked into the gaps and found an important group of people’s lives that have been overlooked or purposefully ingored: Sharony Green, based at the University of Alabama, who has returned the stories of many women of color to the historical discourse. In her book, Remember Me to Miss Louisa, she unpacks the lives of emancipated women in Cincinnati who maintained complicated relationships with their former enslavers. She also discusses other women’s fates, those explicitly sold as concubines. This is distressing history, but we need to understand it to fully understand slavery’s impact on American history. These stories, upsetting as they are, deserve to be told and these lives remembered.

We have spent a lot of time dwelling on the issues of race and race’s role in Frances Wright’s life. This may seem a bit much, a bit obsessive, but we see it as a corrective, rebalancing the France Wright story slightly by providing context and highlighting what has sometimes only been addressed in passing in Fanny’s biography. Nashoba is central to understanding both Fanny’s incredible strengths and impact and her flaws and foibles, dynamics that mirror what we still face today (especially we White women) as we attempt to grapple with America’s cruelest institution.

In the end, I can’t help but wonder at Fanny’s vision of amalgamation as an overwhelmingly positive one, filled with potential joy and even healing, a vission that we might become the single community of caring neighbors, colleagues, friends, family, and lovers that we are called to be.

Next episode, we move from this intersection of race, gender, and sexuality to a topic vital to Fanny: women’s role in marriage and what it means to be a mother and a wife.